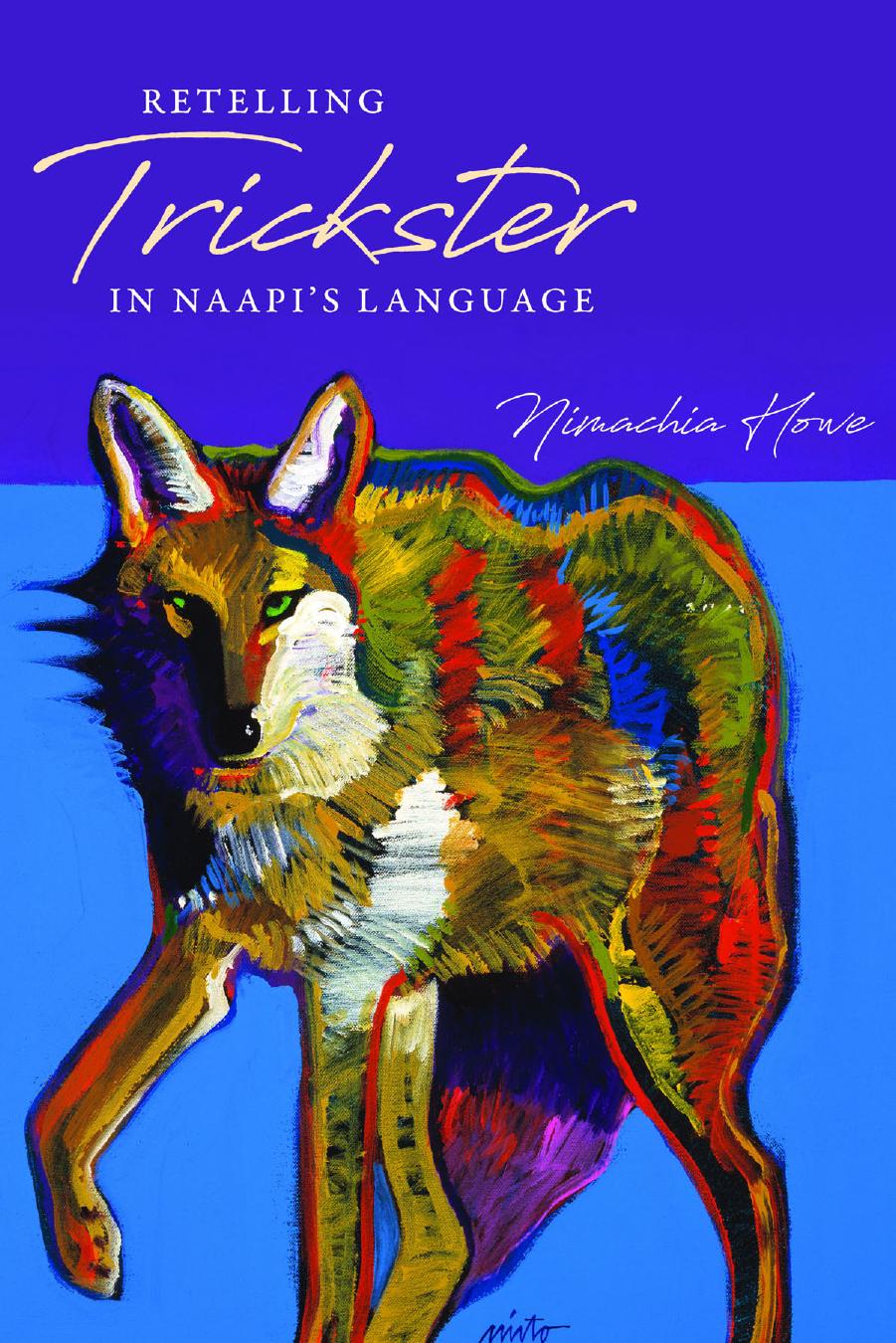

Retelling Trickster in Naapi's Language by Nimachia Howe

Author:Nimachia Howe [Howe, Nimachia]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Tags: Social Science, General, Ethnic Studies, American, Native American Studies, Anthropology, Cultural & Social, Folklore & Mythology

ISBN: 9781607329794

Google: gkm9DwAAQBAJ

Publisher: University Press of Colorado

Published: 2019-10-18T02:44:35+00:00

Land-Based Knowledge

Here, in the land, is where all the explanations and interpretations of the stories reside; but for many displaced Indigenous Peoples, including the Blackfoot, learning from it is complicated, since much of the landscape has been dramatically altered or otherwise changed or destroyed. Similarly, Naapi stories are appropriately considered in reference to site locators and maps, but they are subject to destruction and desecration as it is, so I hesitate to pinpoint them here. Naapiâs âplaygroundâ was drowned with the building of a dam, and his âbowling greenâ has also been altered. The mountains associated with him still hold their place, although his boulders have been removed or destroyed, his animals (e.g., buffalo) greatly diminished, and some birds (e.g., whooping cranes) exterminated, so they no longer have the same impact on the landscape. Nevertheless, as noted earlier, the sum of these locales alone cannot explain Naapi, Trickster-Creator-Destroyer, as place-based analyses alone are limited to land and sites and (once translated into English) to a noun-based space- and place-oriented project that loses the dynamic, unpredictable, âall-overâ aspects of Naapiâs activity.

To begin with, after mapping some specific sites, all sorts of unmappable material remains: climatologically and meteorologically based phenomena, Naapiâs association with winds, stories about Naapiâs sisters, stories that include his female partner/co-creatorâall of which combine to form descriptive and discursive patterns not tied to a specific place. Finally, there are Naapiâs maleness, recurring behavior, unpredictability, regenerative powers, playfulness, and perched-at-the-danger-point positions. Myriad references to Naapi include clues to his âhomeâââwhere he likes to play,â his âsliding place,â his âperch,â how he âfloats,â where he âsleeps,â his âjumping-off pointââand several of his escapades result in his being responsible for the headwaters of trickles, creeks, rivulets, rivers, and similar bodies of water that âgive shapeâ to the homeland and put all people where they belong, also referred to as where they would thrive.3 Waterways map out boundaries. In each of these areas Naapi left his mark or some condition of the land that would be retold in story to recollect the formation and origin of all the coming generations would benefit from because its bounty was so rich and filled every bit of natural space.

Charles M. Russell, a western artist, spent a good deal of time among Indigenous Peoples in and around Montana, including the Blackfoot. Russellâs friend Frank Bird Linderman collected Cree, Chippewa, and Blackfoot creation stories, especially those about Naapi and his equivalents among other Indigenous Peoples. Russell and Linderman witnessed storytelling sessions that Linderman published and that gave Russell background on the Blackfoot worldview, which he used in depictions of Blackfoot in his paintings and sculptures. Russell reflected on Naapiâand his equivalents in Cree and Chippewaâand their creative roles, in particular how an authentic understanding of Naapi would prevent what he saw as virtual sacrilege in apparent war against nature, an attitude of non-Indigenous Peoples:

Download

Retelling Trickster in Naapi's Language by Nimachia Howe.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32538)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31935)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31925)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31911)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19032)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15925)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14476)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14046)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13866)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13341)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13332)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13228)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9313)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9271)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7486)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7303)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6739)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6609)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6260)